ションバーグ黒人文化研究センター

ションバーグ黒人文化研究センター ションバーグ黒人文化研究センターSchomburg Center for Research in Black Culture | |

|---|---|

(2009) | |

| 施設情報 | |

| 正式名称 | Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture |

| 愛称 | ションバーグセンター |

| 前身 | 1905年 135丁目分館 (1925年 黒人文学、歴史及び出版物部門) |

| 専門分野 | 黒人文化、歴史 |

| 事業主体 | ニューヨーク公共図書館 |

| 建物設計 | w:Charles Follen McKim |

| 開館 | 1905 (135丁目分館として) 1925 (「黒人文学、歴史と印刷物部門」として) |

| 所在地 | 西135通り103番地 マンハッタン, ニューヨーク |

| 統計・組織情報 | |

| 蔵書数 | 1千万点(2010年[1]時点) |

| 館長 | Kevin Young |

| 公式サイト | Official website |

| 備考 | |

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture | |

NYC Landmark | |

(2009) | |

| 所在地 | 西135通り103番地 マンハッタン, ニューヨーク |

| 座標 | 北緯40度48分51秒 西経73度56分27秒 / 北緯40.81417度 西経73.94083度 / 40.81417; -73.94083座標: 北緯40度48分51秒 西経73度56分27秒 / 北緯40.81417度 西経73.94083度 / 40.81417; -73.94083 |

| 建築家 | チャールス・フォーレン・マッキム |

| 建築様式 | Italian Renaissance Palazzo|イタリア・ルネッサンスのパラッツォ様式 |

| NRHP登録番号 | 78001881 |

| 指定・解除日 | |

| NRHP指定日 | 1978年9月21日 |

| NHL指定日 | 2016年12月23日 |

| NYCL指定日: | 1981年2月3日 |

| 地図 | |

| |

| プロジェクト:GLAM - プロジェクト:図書館 | |

| テンプレートを表示 | |

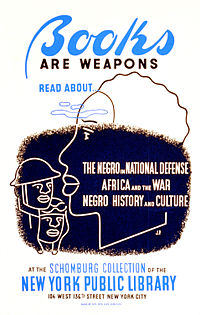

ションバーグ黒人文化研究センター(ションバーグこくじんぶんかセンター、英: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture)はニューヨーク公共図書館の研究図書館のひとつで、世界中のアフリカ系の人々に関する情報の保存機関である。ニューヨーク市マンハッタンに近いハーレムに位置し、レノックス通り(マルコムX通り)515丁目、135丁目通りと136丁目通りの間にある。センターは設立当初からハーレムのコミュニティーに欠かせない存在だった。このセンターはアフリカ系プエルトリコ人の学者アーサー・アルフォンソ・ションバーグに因んで名づけられた。

センターの資料はアートと工芸部門、ジーン・ブラックウェル・ハトソン総合研究調査部門、原稿及びアーカイブと貴重書部門、動画と録音資料部門、写真と印刷物部門の5つの部門に分かれている。

センターでは研究サービスに加え、読書会、ディスカッション、アートエキシビジョン、演劇イベントなどを開催している。センターは一般に公開されている。

初期の歴史

135丁目分館

1901年、アンドリュー・カーネギーなニューヨーク市に65の図書館分館を建設するため5,200,000ドルを寄付することに概ね同意した。市が土地を提供し、建物が完成したら市が建物を管理するという条件だった[2]。1901年の後半、カーネギーはニューヨーク市と契約を結び、図書館を建設するための土地を購入できるよう、市に寄付をした[3] 。マッキム・ミード&ホワイトが建築家として選ばれ、チャールズ・フォレン・マッキムは西135通り103番地にイタリア・ルネッサンスのパラッツォ様式の図書館を設計した[4]。1905年7月14日の開館当時、図書館には10,000冊の図書があり[5]、担当司書はガートルード・コーエンだった[6]。

ローズの在職期間 (1920–1942)

1920年、アーネスティン・ローズ(1880年にニューヨーク州ブリッジハンプトン生まれの白人女性)が分館の司書になった[7]。 彼女はすぐにすべての白人の図書館員を統合した[8] 。ニューヨーク公共図書館に初めて雇用されたアフリカ系アメリカ人のキャスリーン・アレン・ラティマ―は、数か月後、ロベルタ・ボスリー と同じようにローズと共に働くために送り込まれた[9]。しばらくして、サディ・ピーターソン・デラニー が雇われた[10]。同時に、彼らは図書館の利用者の生活と読書を結び付けるよう支援する計画を作り、学校やコミュニティー内の社会組織と協力した[11] 。

1921年、図書館はハーレムでアフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術の初めての展覧会を行った。これは毎年恒例のイベントになった[12]。図書館は急成長するハーレム・ルネサンスの中心になった[8]。1923年、135丁目分館はニューヨーク市で唯一黒人の図書館員を雇用しており[13]、その結果、レジーナ・M・アンダーソンがニューヨーク公共図書館に雇われた時、彼女は135丁目分館に勤務することになった[11][14]。

ローズは1923年、アメリカ図書館協会に報告書を発行し、黒人に関する本や黒人によって書かれたものへのリクエストが高まっており[15] そして専門的な訓練を受けた非白人の司書への需要も高まっていると述べた[16]。 1924年後半、ローズはミーティングを開き、アーサー・アルフォンソ・ションバーグ、 ジェームズ・ウェルドン・ジョンソン、 ヒューバート・ハリソンを含む出席者たちは貴重書の保存にフォーカスし、アフリカ系アメリカ人に関するコレクションを充実させるための寄付を募ると決めた[17]。1925年5月8日、ニューヨーク公共図書館の一部門である「黒人文学、歴史と印刷物」部門としてスタートした[18]。1926年、ションバーグは自身が持つアフリカ系アメリカ人文学のコレクションを一般に公開するために売却したいと考えていた[19]。しかし彼はこのコレクションをハーレムに留めておきたかった[20]。ローズと米国都市同盟はカーネギー財団にションバーグに1万ドルを払いそのコレクションを図書館に寄贈するよう説得した。1926年、ションバーグの個人コレクションが加わったことでセンターのコレクションは高く評価された。コレクションを寄付することで、ションバーグは黒人が他の人種に劣らない歴史と文化を持っていることを証明しようとした[1]。 ションバーグの5,000に上るコレクションが寄付された[21]。

1929年、アンダーソンは昇進を希望したが叶えられず、差別によって昇進できなかったと考え、W.E.B.デュボアとウォルター・フランシス・ホワイトに援助を願った。彼女に代わってデュボアとホワイトが送った書状と、ホワイトによるボイコットの後、アンダーソンは昇進し、リビングトン通りの分館に異動した[22]。

1930年までに、センターは18,000の資料があった[5]。1932年、ションバーグは彼のコレクションの初めての学芸員になり、彼が亡くなる1938年まで在任した[23]。1935年、センターは障害があって図書館に行くことができない人に週1回本を届けるプロジェクトを開発した[24]。ローレンス・D・レディックは黒人文学のションバーグコレクションの2番目の学芸員になった [25]。レドリックの要請により、1940年10月、黒人の歴史・文学及び出版物部門全体がションバーグ黒人歴史文学コレクションと改名された[26]。

1942年、図書館を増築し、図書館の蔵書が40,000冊になった頃、ローズは引退した[27]。ドロシー・ロビンソン・ホーマーは135番通りの市民委員会がローズを黒人の図書館員と置き換えるよう要求したので、彼女を分館の図書館員に置き換えた[28]。

カウンティ・カレン分館

図書館増築後、図書館は「カウンティ―・カレン図書館」分館として知られるようになった[29] 。そして、135丁目分館はカウンティ―・カレン分館の元の場所とみなされているが[30]、その名前は西136通りに拡張された部分にのみ使われている[31]。

ホーマーは青少年向けの本の部屋を作り、地下室にアメリカ黒人劇場を作り、それがブロードウェイに移設されたアンナ・ルカスタ劇場を生み出した。ホーマーはアート、音楽、演劇のコミュニティ・センターを構築することに重点を置いていた。ホーマーはすべての人種の、まだ若く知られていない芸術家の作品を展示した[32]。

第二次世界大戦後、ホーマーは市民の精神を高めるために毎月の演奏会を始めたが、演奏家と観客が練習を続けることを要求したことで継続された[33]。

ハトソンの在職期間 (1948–1980)

1948年、ジーン・ブラックウェル(後のジーン・ブラックウェル・ハトソン)はセンターの所長に指名された[34]。1966年のスピーチで、ハトソンはションバーグコレクションの危機的な状況について警告した[35]。

1971年、センターはションバーグコーポレーションによる民間資金の援助を受け始めた[36]。次の年、ニューヨーク市からの資金は西135通り103番地の建物の改修に充てられ[37]、 その建物の名前も「黒人文化研究のためのションバーグコレクション」と改められた[38]。 同時に、すべてのションバーグコレクションが様々な分館から集められ、センターに送られた[39]。1972年、この図書館はニューヨーク公共図書館の研究図書館のひとつに指定された。

1973年、レノックス通りの135丁目と136丁目の間にある建物を取り壊して新しい施設を建設するために購入された。この立地は他のコミュニティ機関と近く、またハーレム・ルネサンスの舞台だったため選ばれた[40]。1978年、 レノックス通りと7番街通りの間にある135番通りの建物はアメリカ合衆国国家歴史登録財に登録された[41] 1979年、 センターはアメリカ合衆国国家歴史登録財(NRHP)のリストに載った[42]。。

ションバーグ・センター

1980年、新しいションバーグ・センターがレノックス通り515番地に設立された[36]。1981年、ションバーグ・コレクションを保管していた西135丁目の建物は、ニューヨーク市のランドマークに指定された。2016年、元の建物と今の建物は連絡便で結ばれており、アメリカ合衆国国定歴史建造物(National Historic Landmark)に指定されている[43]。

レイの在職期間 (1981–1983)

1981年、 ウェンデル・L・レイがセンターの所長になった[44]。センターの原稿、アーカイブ及び貴重書部門を率いるためにアフリカ系アメリカ人を雇わず、代わりにロバート・モリスを雇うとレイが決定したのをきっかけに抗議が始まった[45]。1983年、例は学術研究を追求するため辞任し[44]、キャスリーン・フッカーが所長代理として指名された[46]。

ドッドソンの在職期間(1984–2011)

ハワード・ドッドソン は1984年に所長になった。そのころションバーグはそこを訪れる観光客や学童の文化施設として知られ、研究機能は学者だけが知っていた[1]。1984年、ションバーグコレクションは500万点に達していた。1984年の1年間の利用者は4万人だった[47]。1984年には、ションバーグ・センターはアフリカまたはその離散者のアートと文学のコレクションのための重要な機関として知られていた[48]。1983年、ションバーグ・センターでは学者の滞在プログラムを開始した[49]。1986年、「Give me your poor...」という展示が論争を巻き起こした[50]。1987年3月、古い図書館を改修し、新しいセンターの機能と環境を高めるための公的資金調達キャンペーンがスタートした[51]。

1991年、ションバーグセンターへの増築が完了した。彼はマルコムX通りの新しいセンターを拡張して講堂を含めるとともに、歴史的建造物の135丁目の古い建物につなげた[52]。 「芸術及び工芸品部門」と「動画及び録音資料部門:は歴史的建物の中に収められた[53]。2000年に、ションバーグセンターは「忘れないように:奴隷制に打ち勝つ」というタイトルの展示を行い、この展示は後にユネスコのスレイブ・ルート・プロジェクトの支援を受けて、10年以上に渡って世界中で開催された。 2005年に、ションバーグセンターはマルコムXに関する手紙、写真などの展示を行った[1]。2007年、1100万ドルのプロジェクトでセンターの建物は改装・増築された。ションバーグセンターは2010年に年間12万人の来館者があった。ドッドソンは2011年早々に退職すると公表した[1]。

2007年、ションバーグセンターはアフリカ人埋葬地国定記念碑のスポンサーの1つだった [54]。

ムハンマドの在任期間 (2011–2016)

| 映像外部リンク | |

|---|---|

Tour of the Schomburg Center conducted by Khalil Gibran Muhammad, May 27, 2015, C-SPAN Tour of the Schomburg Center conducted by Khalil Gibran Muhammad, May 27, 2015, C-SPAN |

ハワード・ドッドソンが2010年に退職を公表した後[1] エリヤ・ムハンマドの孫で、インディアナ大学の歴史学教授の カリル・ギブラン・ムハンマドがドッドソンに代わると公表された[47]。2011年の夏、ムハンマドはションバーグセンターの5番目の館長になった。 彼が掲げた目標は、ションバーグセンターが若者にとって注目の場所になり、地域社会と協力して、その誇りを強化するだけでなく、このセンターが世界中の黒人の歴史を明らかにするためのゲートウェイになることだった[55]。7月、ションバーグセンターは「マルコムX:真実の探求」というタイトルで映像と写真の展示を始めた。

ヤングの在任期間 (2016–現在)

2016年8月1日、ニューヨーク公共図書館は2016年の晩秋に詩人で学者のケヴィン・ヤングがこの図書館の館長になると発表した[56]。

コレクション

ションバーグコレクションは1998年に米国の公共図書館で最も希少で最も有用なアフリカ中心主義の文化遺産であると見なされた[57] 少なくとも2006年後半には、同国の中で最も有名なアフリカ系アメリカ人の資料と見なされている[58]。2010年時点、このコレクションは1000万点の物があり[1]、センターには署名もあり、フィリス・ホイートリーのサイン入り初版本の詩集、メルヴィル・J・ハースコヴィッツ、ジョン・ヘンリック・クラーク[59]、 ロレーヌ・ハンズベリー[60]、 マルコム・X そして ナット・キング・コール[1]のアーカイブ資料があった[61] このコレクションには国際労働者防衛や公民権会議、 新世界の交響楽団[62]、そして全国黒人会議のファイルや論文も含まれていた。また、ローレンス・ブラウン (1893-1973)[63]、ラルフ・バンチ, レオン・ダマス, ウィリアム・ピケンズ,[64] ハイラム・ローズ・レベルス, クラレンス・キャメロン・ホワイトの論文も含まれている。このファイルは南アフリカのデニス・ブルータス防衛委員会(非公開)である[65]。このコレクションには アレクサンダー・クルメル[66]やジョン・エドワード・ブルースの写本、奴隷制度の写本、奴隷制度廃止論と西インド諸島の写本、そしてラングストン・ヒューズの手紙と未発表原稿も含まれていた。 また、コレクションには クリスチャン・フリートウッド、ポール・ロビンソン (制限付き),[67] 、ブッカー・T・ワシントン[68] 及びションバーグ自身の文書が含まれている。 これらには音楽の録音資料、黒人とジャズの定期刊行物、貴重書やパンフレット、何万もの芸術作品が含まれている[69]。 センターのコレクションにはトゥーサン・ルーベルチュール が署名した文書や マーカス・ガーベイのスピーチの貴重な録音資料も含まれる[1]。

ションバーグセンターはクロード・マッケイの文学における相続人代表としても活動している[70]:ix。

関連項目

- ニューヨーク公共図書館

- アーサー・アルフォンソ・ションバーグ

- アーネスティン・ローズ

- ジーン・ブラックウェル・ハトソン

出典

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lee, Felicia R. (2010年4月19日). “Harlem Center’s Director to Retire in Early 2011”. The New York Times. オリジナルの2013年1月30日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://archive.today/20130130150602/http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/19/arts/19library.html?scp=1&sq=Schomburg&st=cse 2012年1月13日閲覧。 ; cf. Rare Library Brought to Harlem: Schomburg's Rare Negro Library Now at the 135th Street Branch Noted Bibliophile Began Collecting Books on His Race 35 Years Ago

- ^ “Carnegie Offers City Big Gift”. New-York Tribune: pp. 1–2. (1901年3月16日). http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1901-03-16/ed-1/seq-1/

- ^ “Library Plans All Right Now: Carnegie Approves Controller Coler Contracts”. The Evening World: pp. 3. (1901年9月9日). http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030193/1901-09-09/ed-1/seq-3/ ; Carnegie Approves the Contracts, Mr. Carnegie's Libraries, The New York Times, September 10, 1901.

- ^ White & Willensky (2000), p. 507; contra: These attribute the original design to Stanford White: "Books, Black Culture and- the Course of History: Books and History", Washington Post, and "'Road to Freedom' Show at Library".

- ^ a b “Library's West 135th Street Branch Will Mark 25th Anniversary Tuesday: Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature Brought Harlem Unit 'to Attention of Book World--Considered Finest”. New York Amsterdam News: p. 3. (1930年7月30日). http://search.proquest.com/docview/226222291

- ^ “New Library Opened”. New-York Tribune: p. 4. (1905年7月15日). http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1905-07-15/ed-1/seq-4/

- ^ Tibbets (1995), pp. 9, 18

- ^ a b Tibbets (1995), pp. 20–21

- ^ Sinnette (1989), pp. 132–133

- ^ Jordan, Casper LeRoy (2000). “African American Forerunners in Librarianship”. In E. J. Josey and Marva L. DeLoach. Handbook of Black Librarianship (2 ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 31

- ^ a b “The Librarian at the Nexus of the Harlem Renaissance”. Atlas Obscura-Stories. Atlas Obscura (2018年3月21日). 2018年3月21日閲覧。

- ^ Wintz (2007), pp. 38–39

- ^ Rose, Ernestine (July 1922). “Work With Negroes Round Table”. Bulletin of the American Library Association 16 (4): 361–366. JSTOR 25686069.

- ^ Whitmire (2007), p. 409

- ^ “Interest Increases In Negro Literature: Miss Ernestine Rose Does Not Believe in Purely Colored Libraries”. New York Amsterdam News: p. 7. (1923年5月2日). http://search.proquest.com/docview/226214352

- ^ Marshall: 67; cf. Working with Negroes Roundtable by Ernestine Rose

- ^ Tibbets (1995), pp. 21–22

- ^ Anekwe, Simon (1978年11月4日). “Schomburg Center, historic property”. New York Amsterdam News: p. A11. http://search.proquest.com/docview/226445221 ; cf. Tibbets: 22, "Historical Society is Launched at Library", 1925-05-13, Sinnette (1989), p. 134

- ^ Sinnette (1989), p. 141

- ^ Sinnette (1989), p. 136

- ^ “Mrs. Latimer in Charge of Negro History Department: Ass't Librarian”. New York Amsterdam News: p. 9. (1927年1月26日). http://search.proquest.com/docview/226371429 ; "2,932 volumes, 1,124 pamphlets, and many valuable prints" cf; Sinnette (1989), p. 141 (New York Library Bulletin 31, April 1927, p. 295).

- ^ Whitmire: ?

- ^ “Schomburg is Buried While Crowds Mourn: Famous Curator Dead at 64; Collected Rare Books, Prints”. New York Amsterdam News: p. 1. (1938年6月18日). http://search.proquest.com/docview/226160559 cf. Schomburg Center History.

- ^ Berlack-Boozer, Thelma (1938年6月18日). “Shut-Ins Cheered By Books From Library: Special Service for Them Operated Only At Busy Branch in West 135th”. New York Amsterdam News: p. 8. http://search.proquest.com/docview/226161624

- ^ “Curator of Negro Literature”. New York Times: pp. 24. (1929年8月23日). http://www.search.proquest.com/docview/102836697 "Dr. Lawrence D. Reddick has been appointed curator of the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library."

- ^ Sinnette (1989), p. 193

- ^ Tibbets (1995), p. 27

- ^ “New Librarian Takes Over At Harlem Branch: Mrs. Dorothy R. Homer, 10 Years on Job, Gets Top Spot at 135th St.”. New York Amsterdam News: pp. 4. (1942年6月27日). http://search.proquest.com/docview/226089714

- ^ “Miss Rhodes [sic, Ernestine Rose] Dies; Integrated Library”. New York Amsterdam News: pp. 4. (1961年4月16日). http://search.proquest.com/docview/225451240

- ^ “About the Countee Cullen Library”. The New York Public Library (2012年). 2011年12月10日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年1月19日閲覧。

- ^ Andrew L. Yarrow, "Repository of Black Past is Reopened", The New York Times, August 19, 1990 (archived).

- ^ Courtney, Charles (1944年12月30日). “Library Tradition Carried On By Dynamic Little Lady: She Heads Popular Uptown Library Branch Civic-Minded”. New York Amsterdam News: pp. 5A. http://search.proquest.com/docview/226038138

- ^ “Doris Earle and Sallee Smith Set For Joint Recital”. New York Amsterdam News: p. 18. (1946年2月9日). http://search.proquest.com/docview/225928025

- ^ “Jean Blackwell Hutson, ex-Chief of Schomburg Center, dies”. Jet 93 (13): 17. (February 23, 1998). https://books.google.com/books?id=VMQDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA17&lpg=PA17&dq=jean+blackwell+hutson&source=bl&ots=_6JjTtG6N-&sig=yzUTilaRSkJe36SwqnhTXrBqLkw&hl=en&sa=X&ei=qcYBT5qkG8bs0gHNwJmADg&ved=0CHEQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=jean%20blackwell%20hutson&f=false 2012年1月2日閲覧。.

- ^ Dodson, Moore & Yancy (2000), pp. 319–320

- ^ a b “Schomburg Center Opens in New York”. The Afro American: p. 13. (1980年10月11日). https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=tSkmAAAAIBAJ&sjid=Sv4FAAAAIBAJ&dq=schomburg%20center&pg=6299%2C1405282 2012年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ “Recalling the Early Days at the Schomburg Center, a Harlem Cultural Hub (page 1 of 2)”. The New York Times. (1987年8月29日). オリジナルの2013年10月6日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20131006031622/http://www.nytimes.com/1987/08/29/arts/recalling-the-early-days-at-the-schomburg-center-a-harlem-cultural-hub.html?src=pm

- ^ “Recalling the Early Days at the Schomburg Center, a Harlem Cultural Hub (page 2 of 2)”. The New York Times. (1987年8月29日). オリジナルの2014年1月11日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20140111222148/http://www.nytimes.com/1987/08/29/arts/recalling-the-early-days-at-the-schomburg-center-a-harlem-cultural-hub.html?pagewanted=2&src=pm ; cf. NYC Landmarks Preservation Committee.

- ^ Dodson, Moore & Yancy (2000), p. 354

- ^ Henderson (1974), p. 78

- ^ Anekwe, Simon (1978年11月4日). “Schomburg Center, historic property”. New York Amsterdam News: pp. A11. http://search.proquest.com/docview/226445221 2011年12月31日閲覧。 ; cf. Stein Lauds Hudson.

- ^ Fraser, C. Gerald (1979年4月1日). “Schomburg Unit Listed as Landmark: Spawning Ground of Talent 40 Seats Are Not Enough Plans for a Museum”. The New York Times. http://search.proquest.com/docview/120941139 2011年12月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Draft NHL nomination for Schomburg Center”. National Park Service. 2017年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ a b “The City; Schomburg Center Loses Its Chief”. The New York Times. (1983年3月10日). オリジナルの2015年5月24日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20150524135800/http://www.nytimes.com/1983/03/10/nyregion/the-city-schomburg-center-loses-its-chief.html 2012年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ “The City; 2 Black Activists Seized in Protest”. The New York Times. (1982年11月19日). オリジナルの2015年5月24日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20150524111617/http://www.nytimes.com/1982/11/19/nyregion/the-city-2-black-activists-seized-in-protest.html 2012年1月2日閲覧。 ; cf. [1]

- ^ Anderson, Susan Heller; Mauricel (1984年1月13日). “New York Day by Day”. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1984/01/13/nyregion/new-york-day-by-day-174899.html 2012年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ a b Lee, Felicia R. (2010年11月17日). “Historian Will Direct Schomburg Center in Harlem”. New York Times. オリジナルの2011年12月19日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20111219191146/http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/18/arts/18director.html 2012年1月13日閲覧。

- ^ “Harlem Renaissance Exhibit Set Saturday at State Museum”. Schenectady Gazette: p. 10. (1984年2月1日). https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=cQ4hAAAAIBAJ&sjid=G3QFAAAAIBAJ&dq=schomburg%20center&pg=2456%2C43736

- ^ “Schomburg Center Scholars-in-Residence Program”. The New York Public Library. 2016年1月18日閲覧。

- ^ “'Liberty' Gala Perplexes Black Patriots”. The St. Petersburg Evening Independent: p. 13A. (1986年6月25日). https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=wbhaAAAAIBAJ&sjid=8VkDAAAAIBAJ&dq=schomburg%20center&pg=4976%2C2605568

- ^ Marriott, Michel (1987年11月23日). “Schomburg Center Acts to Halt Loss of Black History”. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/11/23/nyregion/schomburg-center-acts-to-halt-loss-of-black-history.html?src=pm ; Culture Center Expansion.

- ^ "Grand Opening of Expanded Schomburg Center", The New York Times, April 8, 1991 (archived).

- ^ “Research Complex Expanded”. The Albany Herald: p. 8A. (1991年4月20日). https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=dS9DAAAAIBAJ&sjid=VK0MAAAAIBAJ&dq=schomburg%20center&pg=2561%2C2917879

- ^ “Memorial Dedication: African Burial Ground National Monument”. 2012年1月14日閲覧。

- ^ Barker, Cyril Josh (2011年9月15日). “New director of Schomburg Center gets his feet wet”. New York Amsterdam News. http://www.amsterdamnews.com/news/local/article_56a90284-df21-11e0-abe1-001cc4c002e0.html?cbst=57 2012年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ Kelly, William P. (2016年8月1日). “Introducing the New Director of the Schomburg Center, Kevin Young”. NYPL blog. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2016/08/01/schomburg-director-kevin-young 2016年8月1日閲覧。

- ^ Goedeken, Edward A. (1998). “The Founding and Prevalence of African-American Social Libraries & Historical Societies, 1828-1918”. In John Mark Tucker. Untold Stories: Civil Rights, Libraries and Black Librarianship. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois. pp. 38. ISBN 0-87845-104-8

- ^ Woo, Elaine (2006年10月21日). “A Champion of Black History”. Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/2006/oct/21/local/me-clayton21

- ^ "John Henrik Clarke papers", New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts.

- ^ "Lorraine Hansberry papers", Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

- ^ "Melville J. and Frances S. Herskovits papers", New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts.

- ^ “Symphony of the New World: 50th Anniversary of a Pioneering Organization”. New York Public Library. 2018年7月12日閲覧。

- ^ "Lawrence Brown Papers" at Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

- ^ "William Pickens papers", Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts.

- ^ "Dennis Brutus Papers", Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts.

- ^ "Alexander Crummell Papers", Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts.

- ^ "Paul Robeson collection, 1925-1956" Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts.

- ^ "Booker T. Washington correspondence, 1889-1913", Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts.

- ^ Kaiser, Ernest (2000). “Library Holdings on African Americans”. In E. J. Josey and Marva L. DeLoach. Handbook of Black Librarianship (2 ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. pp. 259–261

- ^ McKay, Claude (2004). Complete poems. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07590-2

Sources

- Howard Dodson, Jr. (Scholars in Residence Program)

- Dodson, Howard; Moore, Christopher; Yancy, Roberta (2000). The Black New Yorkers : the Schomburg illustrated chronology. New York: John Wiley. ISBN 0-471-29714-3. https://archive.org/details/blacknewyorkerss00dods

- Henderson, James W. (1974). The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Its Condition, Operation, and Needs. New York: New York Public Library

- Josey, E. J.; DeLoach, Marva L. (2000). Handbook of Black Librarianship. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-3720-X. https://archive.org/details/handbookofblackl00ejjo_0

- Marshall, A. P. (1976). “Service to Afro-Americans”. In Sidney L. Jackson, Elanor B. Herling, and E. J. Josey. A Century of Service. Chicago: American Library Association. pp. 62–78. ISBN 0-8389-0220-0. https://archive.org/details/centuryofservice0000unse/page/62

- Sinnette, Elinor Des Verney (1989). Arthur Alfonso Schomburg, Black Bibliophile & Collector A Biography. Detroit: The New York Public Library & Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2156-9. https://archive.org/details/arthuralfonsosch00sinn

- Tibbets, Celeste (1995). Ernestine Rose and the Origins of the Schomburg Center. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. ISBN 0-87104-419-6

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot (2000). AIA Guide to New York City. New York: Crown Publishers. p. 507. ISBN 0-8129-3106-8

- Whitmire, Ethelene (2007). “Breaking the Color Barrier: Regina Andrews and the New York Public Library”. Libraries and the Cultural Record 42 (4): 409–421,459.. doi:10.1353/lac.2007.0068. http://search.proquest.com/docview/222598496 2012年1月12日閲覧。.

- Wintz, Cary D. (2007). Harlem Speaks: A Living History of the Harlem Renaissance. Naperville: Sourcebooks. ISBN 978-1-4022-0436-4. https://archive.org/details/harlemspeaks00cary

参考文献

- Harris, Michael H., and Donald G. Davis Jr (1978). American Library History: a bibliography. Austin: University of Texas. ISBN 0-292-70332-5

- Davis, Donald G. Jr, and John Mark Tucker (1989). American Library History: a comprehensive guide to the literature. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc. ISBN 0-87436-142-7

Further reading

- Library Work in Schools 1901-12-18

- Gift To Public Library, The New York Times, 1926-05-26; exact date of the official transfer to the New York Public Library by the Carnegie Foundation at the behest of the National Urban League and Rose

- Books--Authors. The New York Times, 1940-07-26: Description of the donation by Schomburg to the Library in 1926

- Schomburg Collection Bulwark VS Propaganda, 1940

- "Harlem Wants Library Named For Schomburg: Late Bibliophile Gave Impetus to Move Establishing Unit" (1942)

- Eleanor Blau, "Friday A FIENDISH OPENING", The New York Times, Weekender Guide, February 1, 1985 (archived).

- John Jacob, "Black History Month", Washington Afro-American, February 2, 1988.

- Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (not digitized yet)

- Anderson, Sarah A. (Oct 2003). “'The Place to Go': The 135th Street Branch Library and the Harlem Renaissance”. The Library Quarterly 73 (4): 383–421. doi:10.1086/603439. JSTOR 4309684.

- Wilson, Sondra Katherine (1999). The Crisis Reader: Stories, Poetry, and Essays from the N.A.A.C.P.'s Crisis Magazine. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0375752315. https://archive.org/details/crisisreaderstor00wils

- Wilson, Sondra Katherine (1999). The Opportunity Reader: Stories, Poetry, and Essays from the Urban League's Opportunity Magazine. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0375753796. https://archive.org/details/opportunityreade00wils

- Wilson, Sondra Katherine (2000). The Messenger Reader: Stories, Poetry, and Essays from The Messenger Magazine. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 037575539X. https://archive.org/details/messengerreaders00drso

- Girardi, Pamela (2005). The American Historical Association's Guide to Historical Literature.

外部リンク

- Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture - official site at NY Public Library

- Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library at Google Cultural Institute

- "Writings of Hughes and Hurston", broadcast from the Schomburg Center from C-SPAN's American Writers